![]()

Native Peoples, Lewis and Clark, and Mapmaking

-by Herman Viola

Tribes and Culture Areas on the Lewis and Clark Trail

| The Louisiana Purchase nearly doubled the territorial size of the United States. Occupying that vast area were numerous Indian tribes. Although we tend to think of Indians as one people, the tribes Lewis and Clark met were actually very different from one another. Indeed, in terms of language, appearance, and way of life they were as dissimilar from each other as the peoples of Europe. Some of the Indians lived in wooden houses. Some lived in skin houses. Some made wooden boats. Some made boats of bark or animal hides. Some ate dog meat. Others would eat it only if starving. Some tribes were warlike. Others thought war was barbaric. These are "cultural" differences. Tribes that lived near each other, shared a similar way of life, and spoke a similar language are said to share the same culture and are grouped together in a culture area. During their journey to the Pacific Ocean, Lewis and Clark traveled through three different culture areas: the Plains, Plateau, and Northwest Coast. The Plains Indians were primarily nomadic buffalo hunters who lived most of the year in tipis. The horse was an important part of their culture. Although a few of the Plains tribes, like the Mandans and Pawnees, lived in permanent villages most of the year, they hunted buffaloes and had a lifestyle similar to their nomadic neighbors. Among the Plains tribes Lewis and Clark met were the Osage, Sioux, Cheyenne, Crow, and Mandan. Upon reaching the Rocky Mountains, Lewis and Clark entered the country of the Plateau Indians. Living here were the Blackfeet, Flathead, Shoshone, Nez Perce, Spokane, and Yakima Indians. These Indians lived in the Columbia River Country and were fishermen as well as hunters. Upon reaching the Pacific Ocean, Lewis and Clark met Indians of the Northwest Coast Culture Area. These people were excellent wood workers who built large houses, boats, and totem poles. Living near the mouth of the Columbia River were the Clatsop, Tiliamook, and Chinook Indians. |

Lewis and Clark: Ambassadors of Good Will

| Most of the tribes Lewis and Clark encountered were little known in the United States. Many of these tribes, in fact, had become friends with France, Spain, and England before the United States had become a country. It was very important to gain the loyalty and friendship of these tribes for economic as well as military and political reasons. Therefore, President Jefferson instructed Lewis and Clark to make friends and develop trade relations with these Indians as well as collect scientific and military information about them. Lewis and Clark fulfilled their roles as ambassadors of good will to perfection. Whenever they encountered a band of Indians, the captains held a conference, distributed presents, and explained to them that they now owed their allegiance to the United States, not France, Spain, or England. The most important of the presents were certificates, American flags, and Jefferson medals, known as peace medals from the clasped hands of friendship on the obverse. |

|

A Chain of Friendship

| The Corps of Discovery succeeded because of the help of the Indian peoples met along the way. Imagine a chain--its links Indian communities--that stretched from the Mandan villages on the upper Missouri across the Rockies and then along the Columbia River to the Pacific coast. For Lewis and Clark this chain of friendship was a lifeline that enabled them to pass safely through a strange and unknown landscape. The Corps benefited from the protective custody they enjoyed while within the territory occupied by each tribe they visited. From the Indians the explorers received food, an opportunity to rest, and advice about the route immediately ahead. The expedition was particularly indebted to the Nez Perce Indians, who the starving explorers met on September 20, 1805, after their ordeal on the Lolo Trail. Had the Nez Perce been so inclined, the Corps of Discovery could have been erased without a trace. Instead, the Nez Perce fed the explorers and then cared for their horses, which would be needed for their recrossing of the Lolo Trail the following year. |

| After wintering at Fort Clatsop near the mouth of the Columbia River, the Corps of Discovery arrived back in Nez Perce country on June 10, 1806 to find their horses and other belongings in good shape. The Nez Perce not only supplied the explorers with food, but also furnished guides to lead them safely across the trail. One reason the various tribes were so helpful to Lewis and Clark may have been their Indian companion, Sacagawea, and her infant son. This Shoshone woman, married to the French trader Toussaint Charbonneau, accompanied the Corps of Discovery from the Mandan villages to the Pacific Ocean and then came back with them. Indians who might have suspected the explorers were on a warlike mission would have been reassured by seeing Sacagawea and her child with the soldiers. According to William Clark, "The Wife of Shabano our interpreter We find reconsiles all the Indians, as to our friendly intentions. A woman with a party of men is a token of peace." |

|

Native People and Geographical Knowledge

| Of particular benefit to the expedition was the geographical information obtained from the Indians they encountered. For example, on August 14, 1805, at a critical juncture of the expedition, Lewis wrote in his journal: "I now prevailed on the [Shoshone] Chief to instruct me with rispect to the geography of his country. this he undertook very cheerfully, by delineating the rivers on the ground." He did this, Lewis noted, by placing "a number of heeps of sand on each side which he informed me represented the vast mountains of rock eternally covered with snow which the river passed." |

|

In this passage Lewis described the construction of one of the native maps that would guide the Corps of Discovery through the rugged Rocky Mountains by way of the Lolo Trail. In accomplishing this, the explorers had to forsake the relative ease of river travel for hazardous and inclement travel over snow by foot and horseback. |

| Lewis and Clark were not the first explorers to benefit from Indian geographical knowledge. Indeed, from the time of Captain John Smith and Samuel de Champlain, Indians assisted Europeans in the exploration of North America. In this process, Native Americans recorded and transmitted concepts of their cultural, physical, and sacred landscapes using a variety of cartographic devices. These devices took several forms: inscribed maps drawn with charcoal on tanned animal hides or scratched in the ground on snow; raised relief maps modeled with sand, dirt, or snow; and storytelling communicated through sign language. |

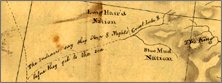

| Sometimes those transitory maps were recorded by explorers or government officials and incorporated in printed maps, in which case Indian geographical concepts were widely disseminated. On the Nicholas King map used by Lewis and Clark on their journey, most information on the American Northwest was based on Indian information. |  |

|

Indian concepts of geographical space differed from those held by Europeans and Americans. The Indian methods of measuring time, distance and direction were based on their experiences as hunters and gatherers. Time and distance were expressed in terms of the number of nights or "sleeps" that it would take to travel from one point to another. Direction was given with reference to the location of the sun. This often led to errors of interpretation by the explorers. |

| For more information on Indian spatial concepts see the following link here. Copyright 2000 Smithsonian Institution and EdGate.com, Inc. All rights reserved. |